Climate Justice in Asia

January 22, 2018

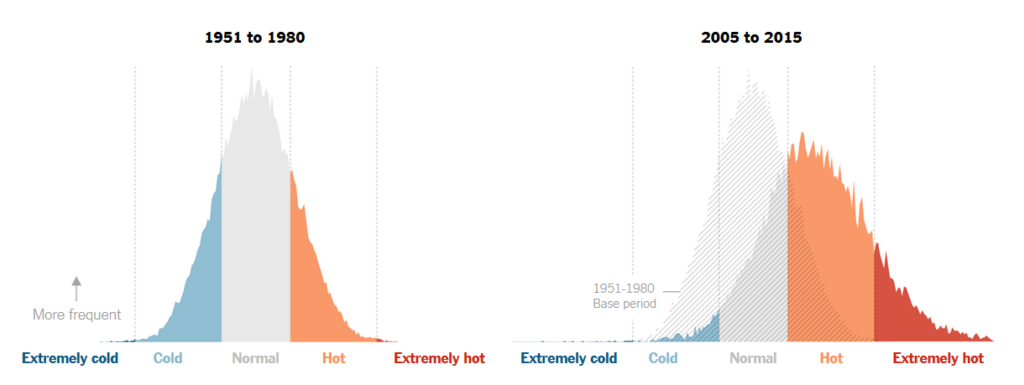

Around the world, summer is getting hotter, threatening the health and lives of poor black and brown people who work or live outside, who have unreliable access to electricity, and who already live in communities surrounded by pollution-spewing vehicles, power plants, refineries, and factories. A recent New York Times piece described data from climate scientist James Hansen showing that, on a spectrum of “cold” to “extremely hot,” the distribution of summer temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere is moving rightward, indicating that there are more “hot” and “extremely hot” summers today than in the middle of last century.

Popovich, N., & Pearce, A. (2017, July 28). Itâs Not Your Imagination. Summers Are Getting Hotter. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/07/28/climate/more-frequent-ext…

Asia has been hit particularly hard. The temperature in a town in southwestern Pakistan reached almost 130 °F in June of this year – during Ramadan, when people were not drinking water or eating during the day. India has experienced several unprecedented heat waves in the last decade that have killed thousands of people, many of whom were outdoor workers. The health effects of exposure to such extreme heat include heat exhaustion, heat stroke, kidney failure, stroke, and the exacerbation of respiratory disease (e.g. asthma, bronchitis) – and mortality. A new study in India finds that, with an increase in summer mean temperatures of just 0.5 °C, heat wave days that kill more than 100 people are two and a half times more likely to occur.

While wealthy people in these countries can opt to stay indoors, in air-conditioned homes, cars, and offices, people who rely on the income from outdoor jobs – construction workers, farm workers, rickshaw drivers, traffic police officers, street beggars – and who cannot afford air conditioning or even reliable electricity that powers fans and refrigerators, lack that freedom. Increased air conditioner use itself contributes to climate change, since the hydrofluorocarbons used as refrigerants are greenhouse gases. Wealthy people are therefore able to avoid the consequences of climate change in a way that worsens it even further, and poor people bear the brunt. This dynamic plays out on the global stage as well, with low- and middle-income countries like India and Pakistan experiencing the consequences of climate change more acutely than high-income countries like the U.S.

Some cities in India have developed plans to cope with increased temperatures and increased heat-related illness among their most vulnerable residents. In 2013, Ahmedabad, a city of 7 million people in Gujarat, developed a groundbreaking Heat Action Plan. It is now on its fifth edition and includes a heat wave early warning system and a “cool roofs” initiative to reduce indoor temperatures; it has inspired other cities to create similar plans.

But extreme heat also coincides with other threats to public health. For example, outdoor workers are also exposed to more ambient air pollution – and of the top ten most polluted cities as measured by fine particles less than 2.5 microns in size, India is home to four (the others are in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Cameroon, and China). Gwalior, for example, is a city with 2 million people in north-central India and is second on the list. The average yearly concentration of fine particles was 176 micrograms per cubic meter, seventeen times the World Health Organization-recommended limit of 10 micrograms per cubic meter. These fine particles, which largely come from vehicle exhaust, irritate the throat and lungs and, ultimately, worsen health conditions such as asthma and heart disease. The double whammy of exposure to extreme heat and high air pollution can be devastating.

These are environmental justice and climate justice issues: trying to unravel them without also unraveling the complexities of poverty, race, and location is impossible. Homegrown solutions like Ahmedabad’s action plan are a good start and can only become stronger by integrating racial and economic justice principles. Even if a woman working as a day laborer knows tomorrow will be extremely hot, her family still depends on her wages – what then? This is a problem beyond the scope of one city in one state in one country. The next step is finding a way to eliminate the impossible choice between health and money, which requires local, national, and global commitments to equity.

About Ragini Kathail