First Nations Leading Land and Marine Stewardship in the Great Bear Rainforest and Sea

January 15, 2018

The Great Bear Rainforest (GBR) stretches from Northern Vancouver Island to the Alaskan border and is the largest intact coastal temperate forest on Earth. Encompassing 6.4 million hectares of the British Columbian Coastline, the GBR and its adjacent marine environment has some of the highest biodiversity in North America, possibly the world. The region boasts healthy populations of sea wolves, spirit bears, humpback whales, old growth cedars, and rare glass sponges that are thousands of years old.

It is understandable that a region as majestic as the GBR would host some of the world’s most significant conservation efforts. At the center of these efforts to maintain ecosystem health and biodiversity are First Nations communities whose ancestors have lived with and managed these environments for millennia. Twenty-six First Nations have traditional territories within the GBR, all with distinct languages, cultural practices, and unique connections to the landscape. Their cultural identity is inextricable from the land and water.

One of the highlights of my Environmental Fellows Program placement with the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation was accompanying my mentor to British Columbia (BC) to visit several First Nations grantees and communities: the Kitasoo-Xaixais, Heiltsuk, Gwa’Sala – ‘Nakwaxda’xw, and Nuxalk Nations. Our group spent much of the time on boats visiting the traditional territories and learning how each community is asserting their indigenous title and rights over their territories to develop and expand their local stewardship and resource management capacity.

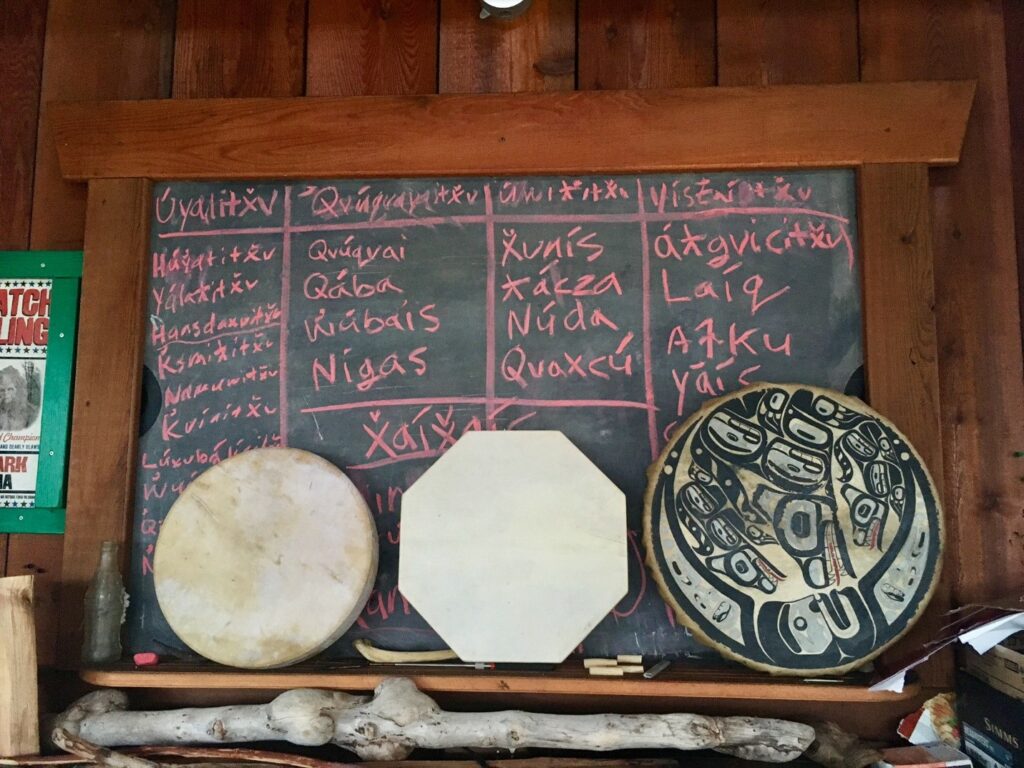

We were updated on the current work being done by the Supporting Emerging Aboriginal Stewards (SEAS) and Coastal Guardian Watchman Network, and were invited guests to the Nuxalk celebration feast for the community book release of “Alhqulh Ti Sputc,” or “Book of Eulachon.” Sputc, the Nuxalk work for eulachon (aka ooligan, or candlefish) are an ecological keystone species, as well as a cultural keystone species, for many First Nations in BC. The Sputc Book began as a research project to address the disappearance of sputc within the Bella Coola River. The project transformed into a book, specifically for the Nuxalk community, which included the customary use, management, celebrations and stories of sputc. The book featured traditional stories and vocabulary in English and Nuxalk, providing a single source holding all Nuxalk knowledge regarding sputc.

The sputc project, along with SEAS and Guardian Watchmen programs, illustrate how First Nations are working with philanthropies to utilize land and marine stewardship and reconnect younger generations to their traditional culture and territory. A new generation of First Nations environmental and community leaders are overseeing these stewardship programs that not only protect their land and sea resources, but also provide mechanisms for rising youth to reconnect with their traditional culture, language and stories. It was clear that land/sea stewardship is an effective vehicle for cultural revitalization and an expression of self-determination. This was a common theme throughout my summer of learning about environmental philanthropy to indigenous communities. During a Canadian Environmental Grantmakers Network (CEGN) panel of indigenous leaders and allies, there was a discussion of how philanthropies could serve as allies to First Nations. Merrell-Ann Phare, Executive Director of the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources, commented that:

“In all the work we have done, the framework or direct goal of programs have not been termed as environmental conservation. They are framed to meet other important community needs such as youth empowerment, supporting aboriginal women, etc. Environmental conservation is a means to meeting these goals.”

Many of the last pristine and biologically diverse areas are located within indigenous territories. Given my summer fellowship observations, to conserve these areas into the future, shifting philanthropic support to projects focused on indigenous self-determination and the durability of cultural identity will advance both justice and, ultimately, conservation outcomes.

About Rachel Smith